Japanese New Year celebrations are heavily rooted in traditions centred around blessings, food, and family, something I can really get around.

If you’re a fellow Aussie, you might be used to entering the New Year a bit wasted, coated in a thin film of sweat, surrounded by friends and strangers, and eventually hungover from the night’s shenanigans. Now maybe it’s my age talking here, but the idea of a tame and spiritual Japanese New Year has slowly become more appealing to me. If you plan on bringing in the new year in the land of the rising sun, here are just a few traditions you may encounter.

Say a little prayer for you

In the first few days of the year, herds of Japanese locals will make their way to nearby temples and shrines to say prayers. This is referred to as hatsumōde (初詣), which literally translates to “first shrine visit” as it is the first visit of the year. At this time, visitors will give thanks to the deities for the previous year and pray for good fortunes for the year to come. Larger shrines often hold festivities that bring a lively atmosphere with food stalls and games for kids, creating a fun and community-filled energy to enter the new year with.

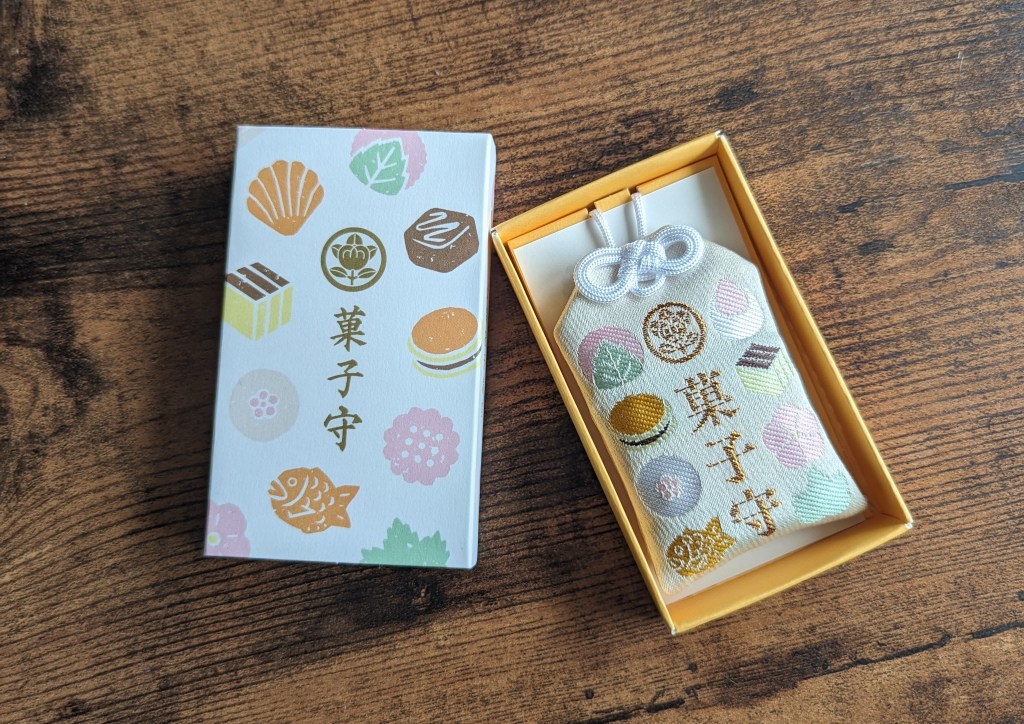

Shrine visitors will also take this opportunity to hand over their omamori from the last year and purchase new ones to provide protection in the new year. Omamori (お守り) get their name from the word mamoru (守る), which means to protect in Japanese. They act as amulets or good luck charms and contain prayers written by the shrine monks wrapped in beautifully designed and embroidered materials with a string for tying onto bags and personal items. Omamori can be purchased in different designs for different purposes at shrines and temples around Japan. For example, you can purchase omamori for wishes and protection around health, pregnancy, academics, finances, travel, and more. I even found one specifically for pastry chefs with the cutest design of different Japanese confectionaries, so it’s worth taking a peek at what each shrine has to offer.

Light em up!

I recently learned of the annual burning of daruma dolls in Gunma, thanks to this post by Tokyo Weekender: https://www.instagram.com/tokyoweekender/reel/DE4cqwWSIQ1/, and now it’s an event on my travel bucketlist.

Last September, I ventured to Katsuo-ji Temple in Osaka to retrieve myself a daruma doll – a symbol of resilience, victory and achieving one’s goal. Here, you take your doll, write a goal or dream that you wish to fulfil in the coming year on it’s back, and colour in the right eye while promising to complete the left eye once the goal/dream is achieved. You then douse the doll in incense smoke from the temple and return home with your new accountability buddy, staring at you with his one eye and reminding you of the promise you made. Customarily, once the daruma has granted your wish, you are to return him to the shrine or you can bring him to the Hatsuichi Matsuri in Gunma to go up in flames as part of a cleansing ritual. Those old omamori that get returned to shrines each year will also go up in sacred flames for the same reason. With all sorts of meanings that come with rising from the ashes and starting anew, I can’t help but be intrigued by this ritual and want to put it into my own practice as I come into each New Year with all of the changes and growth from the last.

Hell bento on good fortune

Now, what’s a good celebration without good food? A catastrophe in my books. I think every year should be brought in with a good meal with good friends and family, and the Japanese know how to do this in style.

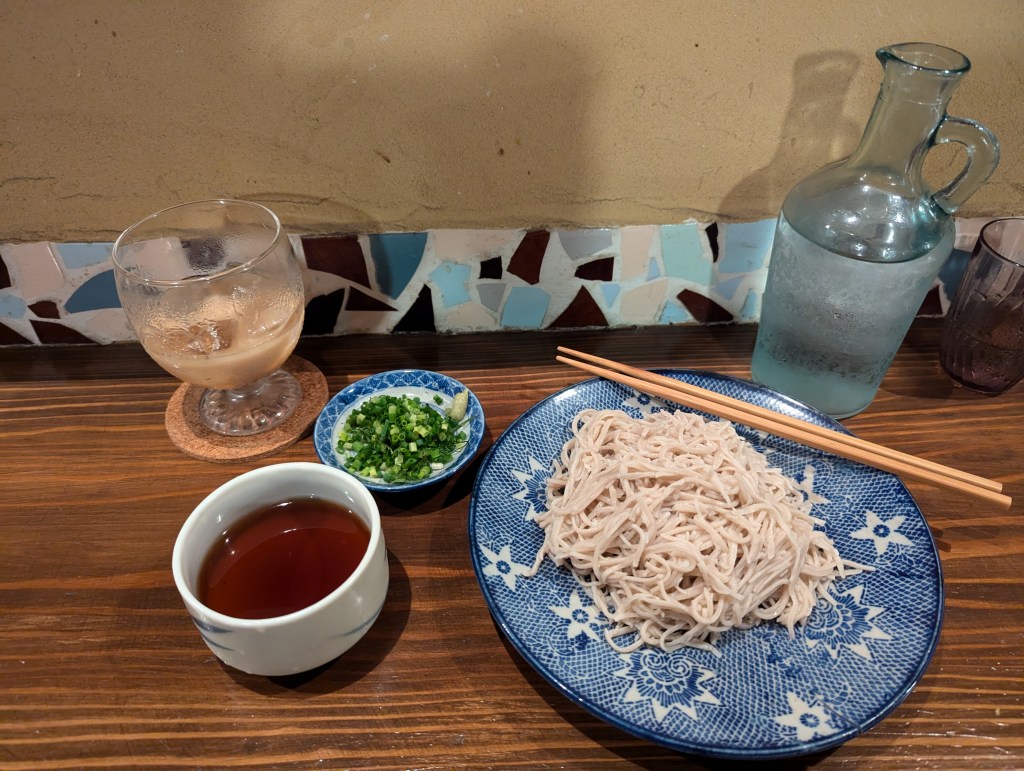

It’s common for Japanese families to chow down on soba noodles on New Year’s Eve to bring good luck and to cut ties with the bad luck from the previous year, since soba noodles are long and thin and break easily. But the real food star of the show is osechi-ryōri (お節料理) – traditional New Year’s food served in a special type of bento box called jūbako. The jūbako are filled with a variety of small Japanese dishes, each symbolising a different wish for the New Year. Some examples of these are kuromame (black beans) for good health, kazunoko (herring roe) for fertility, and ebi (prawns/shrimp) for longevity. The ebi symbol used to make me laugh in university, as the meaning comes from the shape of the ebi resembling and an elderly person bent over, meaning you wish to live a long life until your back is bent. I then stopped laughing when I was coined with the nickname Ebi as it souns similar to Emmy…

Savvy Tokyo has a great list of the different types of osechi-ryōri and the meanings behind them. You can take a peep here if you’d like to learn more: https://savvytokyo.com/osechi-ryori-hidden-meanings-behind-japanese-new-year-food/

If you’ve ever been in Japan on New Year’s, you’ll know that almost everything is shut for three days straight around the holiday. This is meant to be a period for people to take rest from work and, traditionally, to continue eating the osechi-ryōri. Three days of rest AND food? Say no more. Though traditions have changed a little since families have modernised and social lives have become busier, the osechi-ryōri remains a big part of Japanese culture when bringing in the New Year. You can even find osechi-ryōri meals at supermarkets and department stores if you’d like to try one for yourself but aren’t up to the task of cooking several different dishes.

I’m coming into my thirties this year and, while I still enjoy being out on the town and dancing into the morning light, I have a greater appreciation for the kinds of traditions that provoke us to be more mindful and grateful for all that has happened and for what is to come. Society moves at such a fast pace these days that it’s so easy to roll from one day into the next, not stopping to reflect on our lives, our gratitudes, and our wishes. And I don’t know about you but, it feels much better entering the year with good omens and a full belly over dehydration and a splitting headache.

Leave a comment